UCSC scientists collected environmental DNA samples in South Africa as part of the BioSCape project

March 21, 2023

By Rose Miyatsu

Last September, Madeline Slimp had just completed the first year of her Ph.D. program at UC Santa Cruz when she found herself headed on a research trip to South Africa. She was joining her advisor Rachel Meyer, associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, as part of the first team on the ground for a large international project called BioSCape.

BioSCape is run by NASA in collaboration with the South African National Space Agency (SANSA) and the South African Environmental Observation Network (SAEON), as well as other international partners. It aims at combining cutting-edge technology like airborne imaging spectroscopy and lidar remote sensing with field observations to better understand the biodiversity of South Africa’s Greater Cape Floristic Region.

BioSCape is engaging over a dozen different teams to measure everything from soundscapes to levels of phytoplankton in the Greater Cape Region to better understand the role that biodiversity plays in South Africa’s ecosystem. Together, the groups will help NASA create a model for measuring biodiversity changes after disturbances such as wildfires, flooding, species invasion, and climate change.

Tracking biodiversity

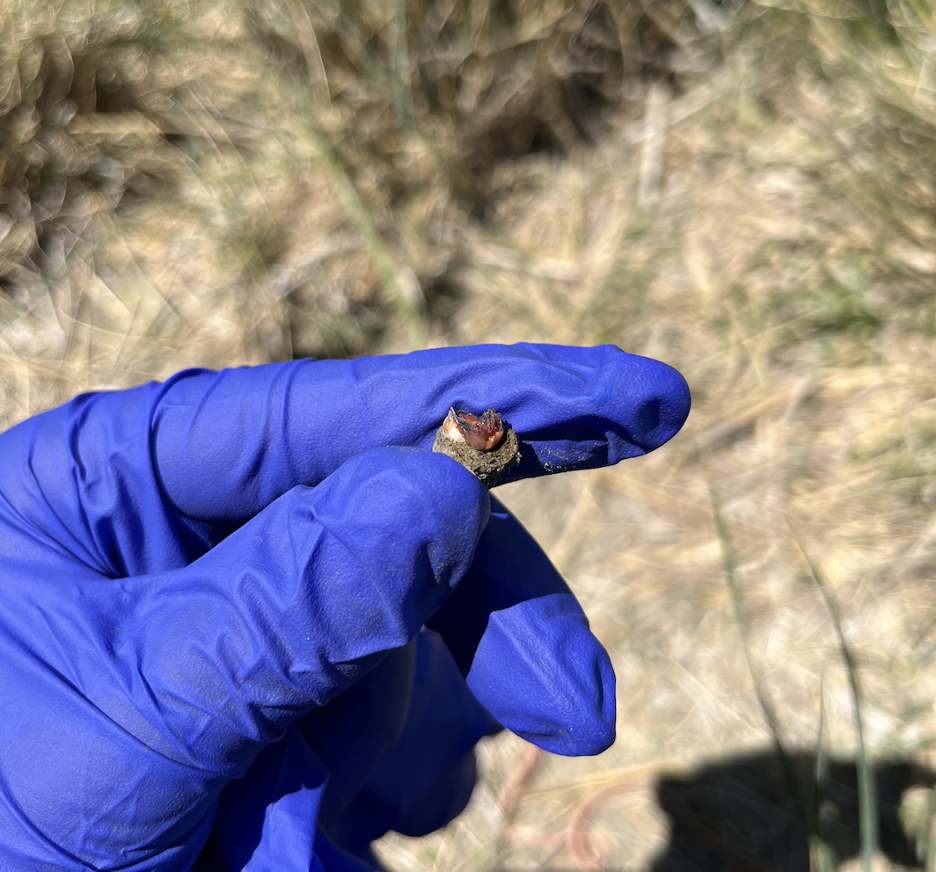

Meyer and Slimp’s role in the BioSCape project is to collect environmental DNA (eDNA) samples along two rivers that run through the Cape. eDNA is a relatively new method for monitoring biodiversity that involves taking soil or water samples from a location of interest, then analyzing those samples in the lab to determine what kind of DNA is present. eDNA only lasts for an average of two weeks before it is degraded, so analyzing what is in the samples gives researchers a good view into what species currently inhabit a given area.

Unlike traditional methods of monitoring species’ presence in a region, which require many hours of observation over a long period of time, eDNA techniques can provide a very clear picture of the biodiversity of an area relatively inexpensively and with only a few site visits. In addition to collecting eDNA for the BioSCape project, Meyer and other scientists in the UCSC Paleogenomics Lab have a number of collaborations with national parks using eDNA to help park managers better understand the areas they are trying to conserve. Their projects have included tracing harmful algal blooms in Alaska, monitoring watersheds in Hawaii, and tracking biodiversity near the Los Angeles River.

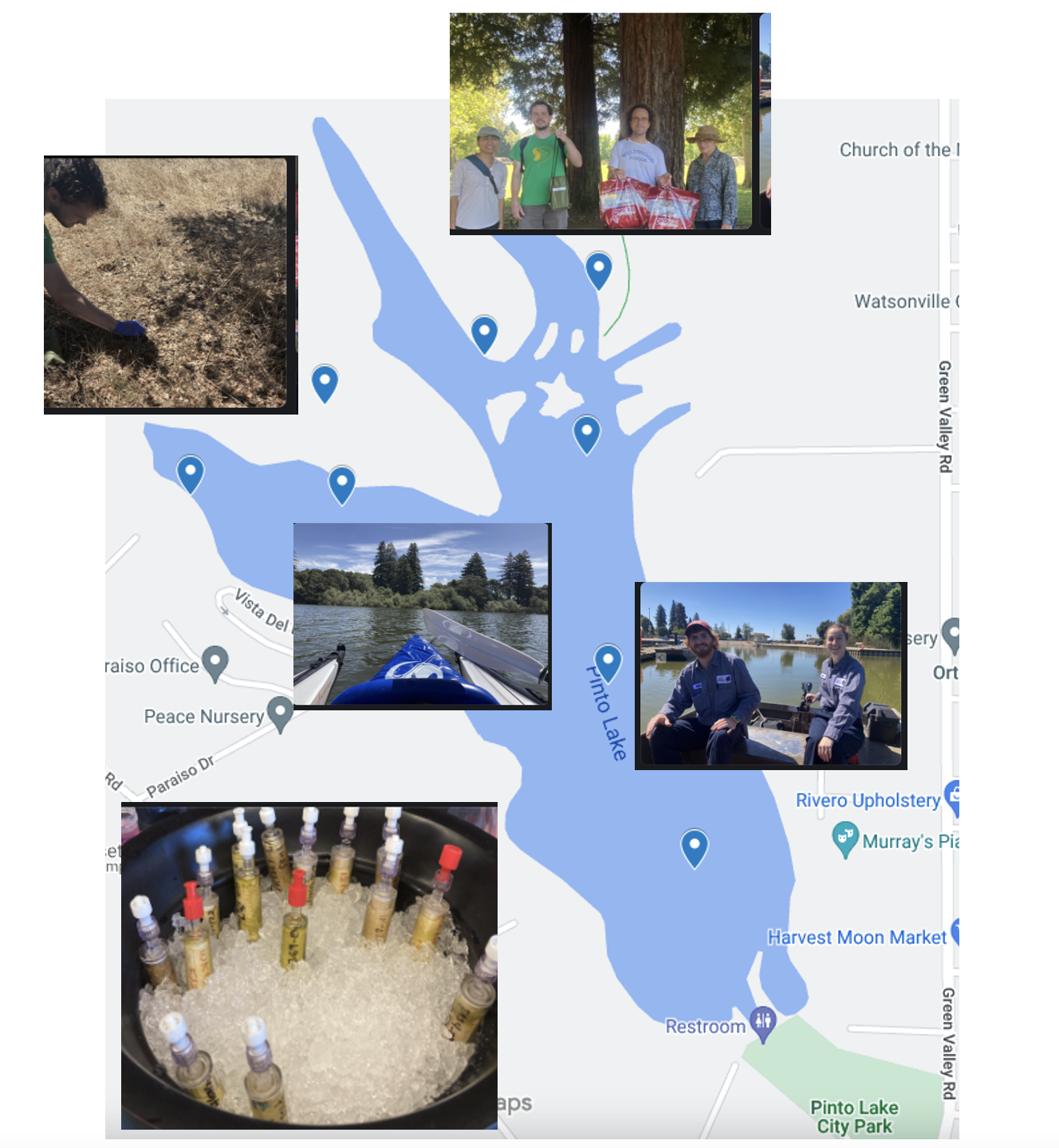

During their trip to the Cape, Slimp and Meyer were joined by several other South African researchers and volunteers to collect samples. They traveled to a total of 34 sites, 30 along a large river called the Berg and four along the smaller Eerste River. The Berg stretches along a diverse landscape that runs from an undeveloped to an urban gradient, much like the Los Angeles River that has been the subject of many previous eDNA excursions. It runs through citrus farms and wineries, and many farmers rely on it to water their crops.

Meyer and Slimp spent more than three weeks in South Africa visiting the collection sites. Some were easily accessible, but others required climbing down 70-degree slopes and wading through rivers to collect their samples. Once their extractions are analyzed, they expect them to reveal which organisms live in and around the Berg and Eerste, and how biodiversity is organized along the river systems. The different sizes of the two rivers will also help them to determine if this organization is scale-dependent.

Adjusting to fieldwork

Because eDNA data needs to be sampled at two different times, both during and after the rainy season, Meyer and her team were the first on the ground for the BioSCape project. This was exciting but came with some challenges, particularly in learning how to communicate the mission of the project to farmers at sites where they wanted to collect data.

“The biggest challenge that I think both Rachel and I had was being outsiders to the culture and political atmosphere of South Africa,” Slimp said. “Being respectful of the culture matters a lot for international research. Listening to the stories of our collaborators has been really important.”

Slimp and Meyer said they felt lucky to have been joined by South African university students and botanists who helped them navigate both the immense biodiversity of the area as well as cultural sensitivities, particularly when asking farmers for permission to take samples on their land.

“Many of the farmers ended up being very receptive,” Slimp said. “They were interested in the project, and when we finished at a site they wanted to know what we found and what was interesting about their land.”

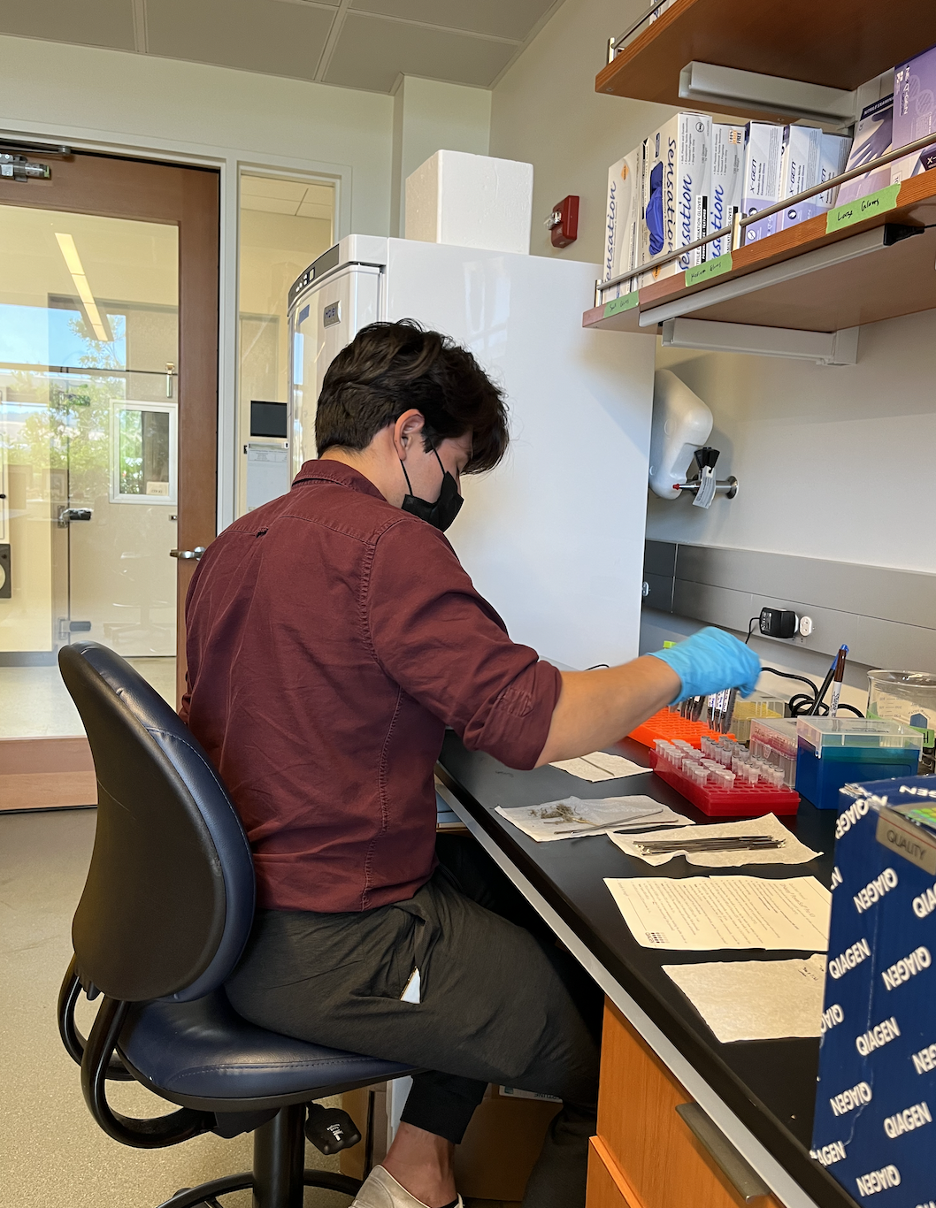

Meyer said that her team was committed to ethically representing South Africa’s interests in their research. For example, the team completes all the DNA extractions from their samples while they are still in South Africa so the samples will stay regulated by South Africa and not the United States.

She is planning to share some of the lessons they learned along the way with other BioSCape partners at a BioSCape conference in May. Many of the other teams have not yet had a chance to collect their samples, and Meyer is hoping that what they share will help them to be more prepared to communicate their own projects in the field. There are also many changing policies that shape how to share access to the collections and data, and how to share benefits from the project. At the conference in May, Meyer and Slimp will be running a session with South African BioSCape teams on benefit sharing and bioethics.

Processing the samples

Meyer and Slimp will embark on a second round of data collection in South Africa in October. In the meantime, there is plenty of work to do processing the extractions that they collected from their first expedition. To learn what is in them, they will match up the DNA they find in their samples with a catalog of “barcodes” of known species.

Barcoding efforts such as the California Conservation Genomics Project and the California Institute for Biodiversity partnerships, which UCSC participates in, have been making large strides in sequencing the genomes and barcodes of as many species as possible so researchers like Slimp can do this type of work. These barcodes are making eDNA an ever-more reliable method for identifying and monitoring biodiversity, even in an area that is as diverse as the South African Greater Cape.

Learning leadership

While a large overseas data collection trip certainly had its challenges, Slimp said she is very grateful for how it helped her develop as a researcher.

“It was a big growth experience,” she said. “It took a lot of strength that I didn’t know I had.”

Slimp was working with two volunteers who had just completed their master’s degrees, Jabulile Malindi from the University of the Western Cape and Ayesha Hargey from the University of Cape Town. Malindi contributed her knowledge on fynbos flora, and Hargey became an expert in eDNA collection, but both were new to eDNA and Bioscape. This placed Slimp in a position of leadership as a teacher.

“I had to step away from being a student and think of the project,” Slimp said. “I have led things before in lab and small-scale data collection, but it was certainly a challenge to have people relying on me for direction, for information, to be a leader. I feel like I am capable of so much more now.”

“I am really excited to go back,” she added. “I just feel so inspired by everyone on the BioSCape team.”

Madeline Slimp’s research is supported in part by funding from the UC Santa Cruz Genomics Institute.